Navigating the Layers of Tooth Decay: From Enamel Erosion to Pulp Preservation Strategies

In the intricate landscape of oral health, the dance of tooth decay is a testament to the complex interplay between environmental factors and biological processes. Tiny invaders relentlessly chip away at the protective outer layers, setting the stage for deeper intrusions and potential pulp harm.

The Silent Breach of Outer Defenses

The Chemistry of Early Mineral Loss

The journey of a cavity begins long before a hole becomes visible to the naked eye. It starts at a molecular level, driven by a constant tug-of-war on the tooth's surface. The oral environment is in a perpetual state of flux, balancing acidity and alkalinity. When we consume fermentable carbohydrates, the natural bacteria in our mouths metabolize these sugars, producing acidic byproducts. This acid creates a hostile environment for the tooth's crystalline structure.

This acidic shift triggers a process known as demineralization. essentially, the acid dissolves the calcium and phosphate minerals that make up the hard, protective shell of the tooth. Under normal circumstances, saliva acts as a natural buffer, rinsing away acids and redepositing minerals in a healing process called remineralization. However, when the frequency of acid attacks outpaces the body's ability to repair, the net loss of mineral content weakens the structural integrity of the surface.

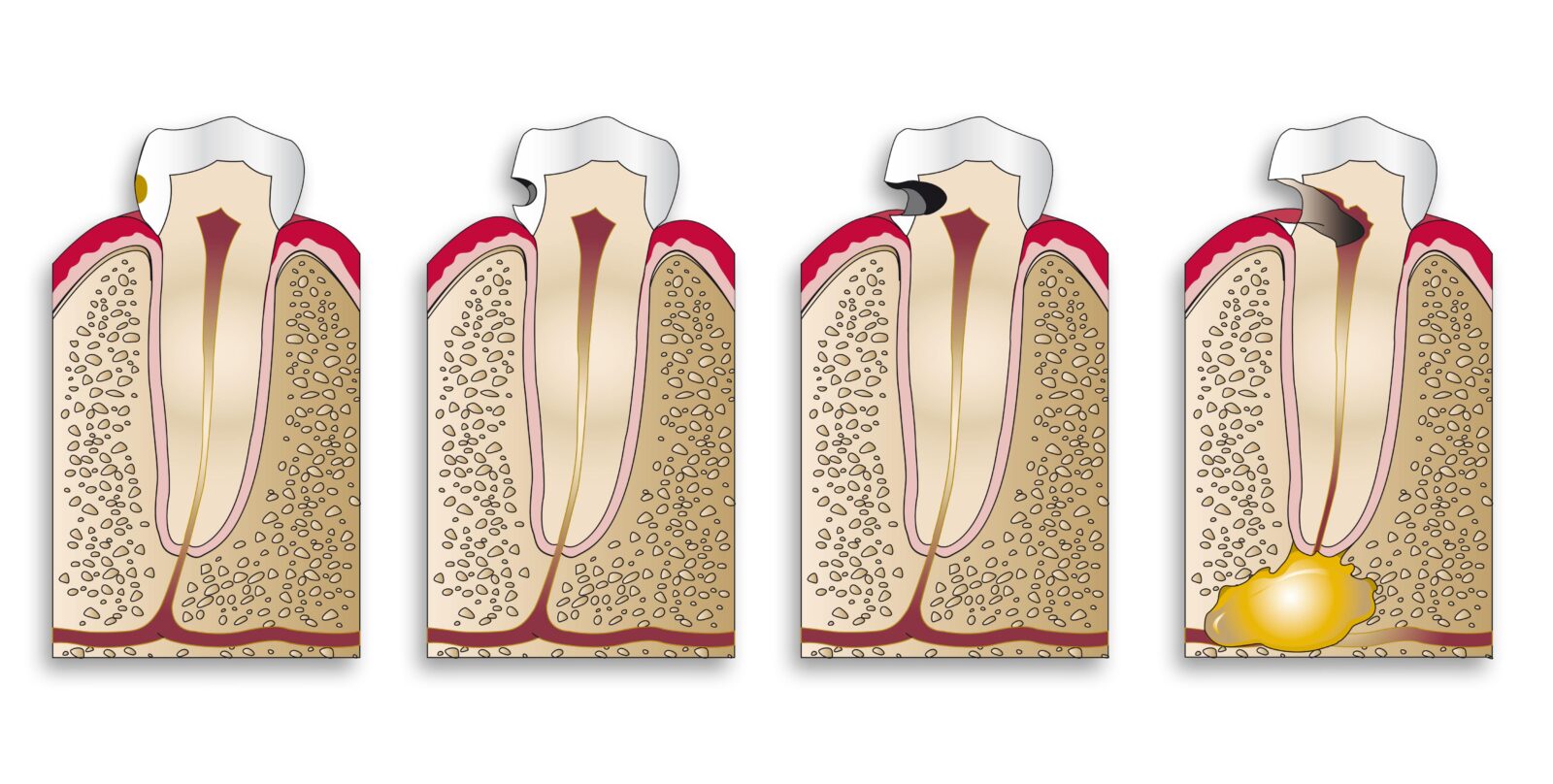

This gradual weakening is often characterized by enamel erosion. Unlike a sudden fracture, this is a slow dissolution. The earliest sign is often a chalky white spot, indicating that the subsurface minerals have been leached away, leaving the outer surface porous and fragile. If this process is not intercepted through dietary changes or fluoride therapy, the structural lattice collapses, forming a physical void. Once the enamel—the hardest substance in the human body—is compromised, the pathway is cleared for decay to advance into the softer, more vulnerable tissues underneath.

The Progression Into the Core

Unraveling the Organic Matrix

Once the decay process breaches the enamel-dentin junction, the nature of the deterioration changes dramatically. Dentin is significantly different from enamel; while enamel is almost entirely inorganic mineral, dentin contains a substantial amount of water and organic material, primarily collagen. Consequently, the destruction of dentin is not just about acid dissolving minerals; it involves a more complex biological breakdown.

As the lesion expands, the dentin undergoes proteolytic degradation. This refers to the breakdown of proteins, specifically the collagen framework that supports the tooth's structure. Bacteria release enzymes that digest this organic matrix, turning the once-hard dentin into a soft, mushy consistency. This stage is critical because the destruction happens much faster in dentin than in enamel. The distinct structure of dentin, which is composed of microscopic channels called tubules, facilitates this rapid spread.

These tubules act as a highway for bacterial ingress. Microorganisms travel down these fluid-filled channels toward the pulp, the tooth's living center containing nerves and blood vessels. As bacteria penetrate deeper, they release toxins that can irritate the pulp even before they physically reach it. The body attempts to defend itself by laying down reparative dentin to block the tubules, but if the bacterial invasion is too aggressive, this natural defense is overwhelmed. The infected dentin becomes a reservoir for bacteria, necessitating mechanical removal to stop the spread.

| Feature | Enamel Decay Characteristics | Dentin Decay Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Composition | Highly mineralized crystalline structure (approx. 96% mineral). | Living tissue with organic collagen matrix and tubules (approx. 70% mineral). |

| Progression Speed | Generally slow; can take months or years to penetrate. | Rapid progression; spreads laterally and deep quickly due to softer structure. |

| Mechanism of Action | Acidic dissolution of mineral crystals. | Combination of acid demineralization and enzymatic breakdown of proteins. |

| Sensory Response | Usually painless in early stages as enamel has no nerves. | Often causes sensitivity to cold, sweets, or pressure due to fluid movement in tubules. |

Advanced Detection and Preservation Strategies

Precision in Diagnosis and Removal

Treating deep decay is a delicate balance between removing the infection and preserving as much healthy tooth structure as possible. In the past, dentists often removed large amounts of tissue to ensure no bacteria remained, inadvertently weakening the tooth. Modern dentistry, however, utilizes more refined techniques to distinguish between layers of decayed tissue.

One of the challenges in excavation is identifying the boundary between "infected" dentin (which is soft, loaded with bacteria, and cannot be saved) and "affected" dentin (which is demineralized and stained but bacteria-free and capable of remineralizing). To aid in this visual distinction, clinicians often utilize a caries detector dye. This diagnostic solution penetrates the porous, infected collagen network that has been denatured by bacterial enzymes. By staining the irreversibly damaged tissue while leaving the healthy or reparable dentin unstained, the dye acts as a map. This allows for minimally invasive preparation, ensuring that only the tissue that absolutely must go is removed, maintaining the structural strength of the tooth.

Safeguarding the Vital Nerve

When decay reaches deep near the nerve, the risk of exposing the pulp increases. A pulp exposure often necessitates a root canal treatment, a complex procedure removing the nerve entirely. To avoid this when possible, restorative dentistry has developed vital pulp therapy techniques.

If the decay is deep but the pulp is not yet irreversibly inflamed, a dentist may opt for an indirect pulp cap. This procedure involves leaving a thin layer of affected (but not infected) dentin over the nerve rather than risking exposure by scraping it all away. A biocompatible material is then placed over this layer. These materials often release calcium or fluoride and create a seal that starves any remaining few bacteria of nutrients.

This approach relies on the tooth's remarkable ability to heal. The medicated lining stimulates the pulp cells to produce tertiary dentin, a new protective layer of hard tissue that pushes the nerve further away from the danger zone. By prioritizing the biological seal over total mechanical removal near the nerve, the tooth remains vital and functional without invasive endodontic therapy.

Q&A

-

What is demineralization, and how does it affect dental health?

Demineralization is the process where minerals, primarily calcium and phosphate, are lost from the tooth enamel. This occurs due to acidic environments often created by bacterial metabolism of sugars. The loss of these minerals weakens the enamel and can lead to enamel erosion and increased susceptibility to cavities and decay.

-

How does enamel erosion differ from demineralization?

While demineralization is the initial stage of mineral loss from the enamel, enamel erosion refers to the more advanced and irreversible damage that occurs when the enamel is worn away. This can result from prolonged exposure to acidic substances, both dietary and bacterial, ultimately leading to tooth sensitivity and aesthetic concerns.

-

What role does proteolytic degradation play in dental health?

Proteolytic degradation involves the breakdown of proteins in the tooth structure, particularly the dentin, by enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases. This process can compromise the structural integrity of the tooth, facilitate bacterial ingress, and contribute to the progression of dental caries.

-

How is a caries detector dye used in dental procedures?

A caries detector dye is a diagnostic tool used by dentists to identify areas of demineralized tooth structure and decay. The dye selectively stains infected dentin, helping to differentiate between affected and healthy tissue, ensuring that only the decayed portions are removed during restorative procedures.

-

What is an indirect pulp cap, and when is it used in dentistry?

An indirect pulp cap is a dental treatment applied when a cavity is close to the pulp but does not expose it. It involves placing a protective dressing over a thin layer of remaining dentin, aiming to preserve pulp vitality and promote the formation of secondary dentin. This procedure is often used to prevent the need for more invasive treatments like root canals.