Navigating Pericoronitis: From Operculum Inflammation to Surgical Solutions

The discomfort associated with partially emerged lower jaw teeth often presents a complex challenge for young adults. Addressing this involves a delicate balance of timely action and precision, as simple discomfort can swiftly escalate into more severe conditions requiring more intensive solutions to ensure optimal oral health.

Unmasking the Hidden Discomfort

Decoding the Symptoms of Jaw stiffness and Infection

The journey of wisdom tooth trouble often begins subtly, with a dull ache in the retromolar region that is easy to ignore. However, this discomfort can rapidly evolve into a more debilitating condition. One of the most alarming signs for patients is the sudden inability to open the mouth fully, a condition clinically known as trismus. This occurs when the inflammation spreads from the gum tissue into the muscles of mastication (chewing muscles), causing them to spasm. Attempting to force the jaw open during this state results in sharp pain, making eating and speaking incredibly difficult.

Beyond the mechanical restriction of the jaw, the biological signs of infection are often palpable. Patients frequently report a foul taste or halitosis, caused by purulence (pus) draining from beneath the swollen gum tissue. The body’s immune response may also trigger systemic symptoms, such as fever and swollen lymph nodes in the neck and submandibular area. These are not merely symptoms of a "bad tooth" but are indicators that the body is actively fighting a bacterial invasion. Recognizing these signs early—rather than dismissing them as temporary sensitivity—is crucial for preventing the spread of infection to deeper facial spaces.

The Structural Trap: Why Timing Matters

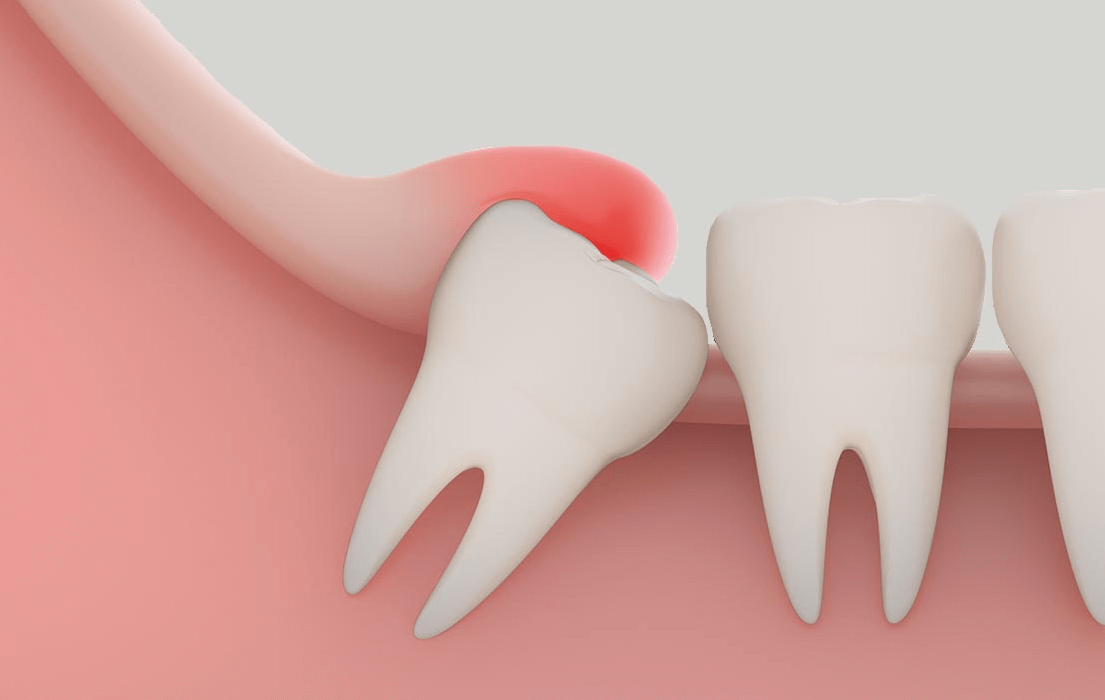

The root cause of this inflammation lies in the mismatch between dental anatomy and jaw evolution. Third molar eruption typically occurs between the late teens and early twenties, a period when the jawbone has largely completed its growth and the dental arch is already occupied by 28 other teeth. In modern populations, the jaw often lacks the necessary dimensions to accommodate these final molars, leading to impaction.

Because of this spatial deficit, the tooth may only partially breach the surface, creating a "soft tissue hood" or flap over the tooth's crown. This anatomical structure creates a perfect incubator for bacteria. Unlike a fully erupted tooth where the gum attaches neatly to the neck of the tooth, a partially erupted tooth creates a deep, unreachable pocket. Food debris and plaque accumulate here, and because the opposing upper tooth often bites down onto this swollen tissue, the cycle of physical trauma and bacterial stagnation perpetuates the infection. This structural trap is the primary reason why these issues tend to recur until the physical environment is altered.

First Line of Defense: Hygiene and Conservative Care

Immediate Relief and Debridement Strategies

When acute symptoms strike, the primary goal is to reduce bacterial load and manage inflammation before considering invasive procedures. At home, patients are often advised to utilize warm saltwater rinses. The osmotic effect of the salt helps reduce edema (swelling) in the tissues, while the mechanical action of rinsing flushes out superficial food particles. It is vital, however, to avoid applying external heat to the jaw, as this can draw more blood to the area and potentially exacerbate the swelling. Over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medications are frequently used to manage pain and allow the patient to open their mouth wide enough for hygiene.

In a clinical setting, the focus shifts to soft tissue debridement. This involves the professional irrigation of the space between the gum flap and the tooth using sterile saline or antimicrobial solutions like chlorhexidine. This process flushes out the trapped debris and bacterial colonies that a toothbrush simply cannot reach. If the infection is substantial or systemic symptoms are present, a short course of antibiotics may be prescribed to control the bacterial spread. This phase is about "cooling down" the angry tissue to make the patient comfortable and to prepare the site for potential future treatment.

| Feature | Home Care Management | Professional Conservative Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Symptom mitigation and surface hygiene | Deep cleaning and infection control |

| Key Methods | Saltwater rinses, analgesics, gentle brushing | Sub-gingival irrigation, antibiotics, debris removal |

| Limitations | Cannot access deep pockets; temporary relief | May not resolve structural causes; recurrence possible |

The Silent Risk to Adjacent Teeth

While the immediate pain of the wisdom tooth is the patient's main concern, the condition poses a significant silent threat to the neighboring second molar. The pocket formed by the impacted wisdom tooth is a reservoir for plaque that sits directly against the back surface of the healthy tooth in front of it. Because this area is impossible to clean with floss or a brush, it often leads to distal caries (cavities on the back surface) on the second molar.

This is a critical aspect of conservative care assessment. If the waiting game continues for too long, the patient risks losing not just the troublesome wisdom tooth, but also the vital chewing tooth adjacent to it. Therefore, conservative management is rarely viewed as a permanent solution for young adults with structurally compromised impactions. It is a holding pattern designed to resolve acute pain, allowing for a clearer assessment of whether the wisdom tooth needs to be removed to protect the overall integrity of the dental arch.

The Surgical Crossroads: Moving Beyond Temporary Fixes

Evaluating the Surgical Options

When conservative measures fail to prevent recurrence, or when the anatomical risks are too high, surgical intervention becomes necessary. The decision-making process involves detailed imaging to assess the position of the tooth and the shape of the gum tissue. One minor surgical option is an operculectomy, which involves excising the flap of gum tissue covering the tooth to eliminate the pocket where bacteria hide. This addresses the immediate operculum inflammation and can be effective in cases where the tooth is upright and has space to erupt fully.

However, for many patients, removing the tissue is only a temporary fix. If the tooth remains impacted or positioned at an awkward angle, the gum tissue often regrows, or the pocket remains deep enough to trap food. Furthermore, if the opposing upper tooth continues to traumatize the lower gum, simply trimming the tissue may not resolve the mechanical irritation. Consequently, while less invasive, this approach is carefully selected for specific candidates and is not the universal solution for impaction-related infections.

The Gold Standard: Surgical Extraction

For the vast majority of recurrent cases, surgical extraction of the offending wisdom tooth is the definitive treatment. This procedure removes the source of the infection entirely. By extracting the tooth, the dentist eliminates the impossible-to-clean pocket and the physical barrier causing the inflammation. Modern surgical techniques, often utilizing sectioning (cutting the tooth into smaller pieces) and bone preservation methods, have streamlined this process, significantly reducing trauma to the surrounding tissues.

| Consideration | Gum Tissue Excision (Operculectomy) | Complete Surgical Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Scope of Procedure | Removal of the infected gum flap only | Complete removal of the source tooth |

| Recurrence Potential | Moderate (tissue may regrow) | None (source eliminated) |

| Long-term Outcome | Retains the tooth; relies on proper eruption | Permanent resolution of localized infection |

The timing of this surgery is critical. Clinical consensus suggests that prophylactic removal in young adulthood is preferable to waiting for emergencies in later life. Younger patients typically have softer bone, which makes the extraction easier and the healing process faster. Delaying extraction until after repeated cycles of infection can lead to denser bone, increased risk of complications, and a higher likelihood of creating defects behind the second molar. Ultimately, transitioning from conservative management to a surgical solution is often the most predictable path to restoring oral health and preventing chronic pain.

Q&A

-

What is operculum inflammation, and how does it relate to third molar eruption?

Operculum inflammation, also known as pericoronitis, occurs when the gum tissue around a partially erupted tooth becomes swollen and infected. This condition is commonly associated with the eruption of third molars, or wisdom teeth, as they often do not have enough space to emerge fully, leading to gum irritation and bacterial infection.

-

How can trismus be a complication of third molar eruption, and what are its implications?

Trismus, or the limited ability to open the mouth, can occur due to inflammation or infection associated with the eruption of third molars. This condition can impede oral hygiene and complicate dental procedures, making it necessary to address the underlying causes, such as infection or inflammation, to restore normal mouth function.

-

What role does soft tissue debridement play in managing operculum inflammation?

Soft tissue debridement involves the careful removal of infected or inflamed tissue around the operculum. This procedure helps reduce bacterial load, alleviate symptoms of pericoronitis, and promote healing. Regular debridement may be necessary to manage chronic inflammation and prevent further complications during third molar eruption.

-

Why are distal caries a concern during third molar eruption, and how are they treated?

Distal caries, or cavities located on the back surfaces of teeth, can develop due to the difficulty in cleaning areas near partially erupted third molars. These caries are often treated with fillings, but in some cases, extraction of the third molar may be recommended to prevent further decay and maintain oral health.

-

When is surgical extraction considered necessary for third molars, and what are the potential benefits?

Surgical extraction of third molars is considered when they are impacted, causing pain, infection, or damage to adjacent teeth. The procedure can prevent recurrent infections, alleviate pain, and reduce the risk of cysts or tumors. It is often recommended when conservative treatments are ineffective or when the third molars pose a significant risk to oral health.